Home brews

By David Godkin

Business Operations Food Trends Beverages beer brewing print issue - Food in CanadaCanadian breweries are offering new ways of thinking about beer

Facts, someone once said, are stubborn things. The hardest fact facing Canadian brewers is that their share of the alcoholic beverage market has been slipping – from 52 per cent in 2000 to 45 per cent in 2011, according to Statistics Canada. The wine industry, meantime, has been more than pleased to take up the slack, blossoming from 23 to 30 per cent in market share over the same period.

It’s easy enough for beer companies to explain the drop by pointing to changing demographics, nimble-footed wine campaigns and consumer concerns over health. How to reverse the trend is another matter entirely. One thing everyone agrees on is that reviving the industry’s fortunes requires new ways of thinking about beer.

Through the glass darkly

According to Statistic Canada by 2036 a quarter of Canadians will be aged 65 or older, compared to 14 per cent in 2012. That means more people concerned about their widening waist bands will be turning away from beer. But consider that an aging population also means a more sophisticated, more demanding consumer. That, says Laura Urtnowski, president of the Association of Micro Brewers of Quebec (AMBQ),

continues to be the Canadian brewing establishment’s biggest stumbling block. “Since the big guys make such great volumes they have to rely on brand loyalty and people drinking only Coors Light,” she says. “But that’s not happening anymore. There’s a lot less brand loyalty because people simply want to try new stuff.”

Enter a new business model, the microbrewery, created in the 1990s and floating on an array of “new stuff” from cranberry beer flavours to nut browns, from black-style beers to porters. For years craft beer was largely ignored by the Big Three, Labatt, Molson and Moosehead, says Urtnowski, adding, “I remember them saying craft beer was going to go belly up, and ‘Look at that beer, it’s got a funny colour to it.’” But the problem was not just the contempt the majors felt for the different flavoured beers; the beer industry, says Moosehead vice-president of Sales and Marketing Matt Johnston, “failed to adapt to the changing consumer.”

Molson president and CEO Dave Perkins agrees, noting that too often the industry focused on “legal drinking age to 29 year old males.” “We forgot about the older male consumers and females, and so today you see an awful lot of marketing activity and innovation designed to broaden the appeal, to be more inclusive with beer.”

Now everyone is getting the message, none more clearly than André Fortin, director of Public and Government Affairs for the Brewers Association of Canada. “Where my grandfather used to drink the same beer over and over again, I find myself willing to try different things,” says Fortin. But the best testament to that effort may be the eagerness of the three majors to broaden their own offerings and experiment with the taste of beer. In 2010 Molson purchased Granville Island Brewery. Labatt acquired Goose Island. Moosehead, meanwhile, launched Hop City Brewing, a new craft division that introduced Barking Squirrel Lager, a medium body lager the company describes as “Craft with Attitude.”

Telling the story of beer

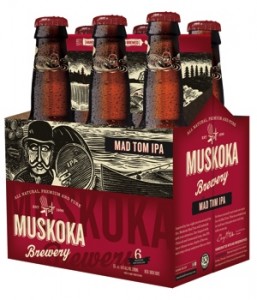

Aggressive marketing has helped the wine industry communicate the tremendous variety and sophistication of wine to an ever-appreciative audience. By contrast, the story of beer, says Gary McMullen, head of the Ontario Craft Brewers Association and Muskoka Brewery, has been consigned to studly young men surrounding T-shirted babes in beer parlours. How beers are made, where they’re made and their enormous variety tell a different story, he says. Beer is no longer the “yellow fizzy beverage sold in a brown bottle. Now beer is a dark stout, a very, very light lager, it’s a wheat beer or our own double chocolate cranberry stout, an eight-per-cent beer that rivals some wines in alcohol content,” says McMullen. “That’s the story that needs to be told.”

That story also needs a colourful cast of characters, says Frédérick Tremblay. The owner of MicroBrasserie Charlevoix in Baie-St-Paul, Que. devotes an entire online TV show to things Quebec brewers do when they’re not tending their beer vats (Tremblay plays a mean blues harp while Urtnowski is seen on horseback leaping fences in the Quebec countryside). “We think it’s one of the things that’s going to set us apart from the big guys,” Tremblay explains.

A plot line that helps wine but hurts beer is consumer perceptions about what is and isn’t good for them. Where wine is awash in free publicity touting the beverage’s contribution to heart health, beer has been saddled with warnings about caloric content and the link between grain and celiac disease. Hampered by federal regulations preventing too close an advertising link between good health and beer, the industry has had to content itself with listing health-giving ingredients in tiny print on their beer labels.

Undeterred, some companies are reaching out more boldly to health-conscious consumers. A case in point: Labatt’s Michelob ULTRA. At 2.6 g of carbs and 95 calories ULTRA is aimed, says marketing director Arielle Loeb, at people who love to exercise but love their beer, too. “There are a lot of people out there who are active even as they get older, and this is a beer that suits that lifestyle.” While Tremblay can’t abide low-cal beers, gluten-free beer “has a very, very big future,” he says, but only if manufacturers can make a gluten-free beer that’s also flavourful.

If you can’t beat ’em, feed ’em

Beer marketers tell us that more consumers are going to the beer store asking the same question wine lovers ask: “I know what I’m going to eat

tonight. But what am I going to drink with it?” Johnston says food will play a bigger role in consumers’ beer habits as they retire and spend more time at home. “They may want an ultra-light beer for when they’re done mowing the lawn, but sit down with dinner and have a more flavourable pale ale. They have a little more disposable income, a little more time on their hands and are romancing their food.”

“There are so many beer styles out there people are recognizing that it affects the flavour of foods and want to get it right,” agrees Tracey Larsen, co-owner of Mt. Begbie Brewing Company in Revelstoke, B.C. “If you’re going in the fish direction a lighter-bodied, more delicate-flavoured beer would be good. Conversely, a brown ale would be better with good strong cheeses or beef.”

Other brewers are also getting in on the trend. Labatt Blue is not just for burgers anymore says a recent ad – it also makes a refreshing match with hot wings and Mexican fare. And where Molson Coors pairs its Cobra Beer with Indian food, McMullen swears by Muskoka Brewery’s cream ale in combination with roasted chicken, and its Mad Tom IPA with smoked salmon. Are consumers surprised by this? McMullen doesn’t think so, especially as wine has been making these kinds of pairings for years. But even that industry is changing. The trick, McMullen says, is to stay current on what’s happening throughout the food and beverage industry, including in wine, beer and agriculture. “The fresh local food phenomenon, for example, has generated even more interest in wines,” he says. “I think there’s a product story for beer there as well.”

Print this page