COVID-19: Regaining trust of citizen-consumers through effective signalling

By John G. Keogh

Food In Canada Research & Development COVID-19

By John G. Keogh

March 18, 2020, Toronto, Ont. – In a global pandemic like COVID-19, a considerable knowledge gap or information asymmetry opens up between citizen-consumers, governments and public health agencies (PHAs). Amid a plethora of message distortions across the media landscape, citizen-consumers trust in the guidance provided by the government, and their PHAs, is affected by the perceived congruence of the communications (i.e. signals).

In this article, I summarize the utility of signalling theory and briefly discuss empirical evidence describing personal control deprivation, which leads to panic buying and hoarding of utilitarian products like food and cleaning supplies. I propose that signalling theory offers a useful framework to improve crisis communications. The article concludes with five recommendations.

The critical role of Signaling Theory

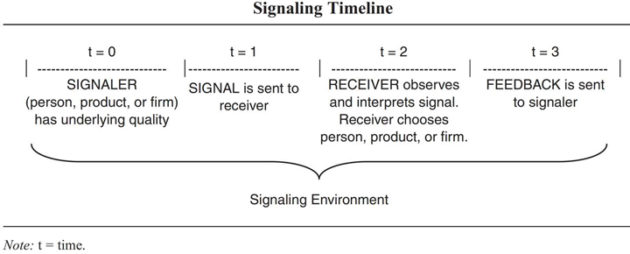

Signalling theory emerged from the study of information economics to address information asymmetries (i.e. gaps) that occur between two parties, such as brands and consumers or governments and citizens. Its primary utility is to reduce information asymmetries, and it helps to describe behaviours that occur when parties have access to different information. Signalling theory can help to guide us on how to measure the effectiveness of public health communication, including how to watch for signal distortion and to ensure signal recalibration based on a critically important feedback loop. In their Signaling Timeline model (below), Connelly et al. (2011) note, “Typically, one party, the sender, must choose whether and how to communicate (or signal) that information, and the other party, the receiver, must choose how to interpret the signal.” The key elements of signalling consist of (1) a signal sender or signaller such as a PHA, (2) a signal such as infection prevention guidelines and (3) a signal receiver, citizen-consumer-patient and (4) the feedback loop. The graph below depicts the signal timeline, emphasizing the importance of step 4, the feedback loop and the signalling environment where noise and signal distortion can occur.

In a crisis, active signalling can play a crucial role in reducing information asymmetry, allaying societal fears and enhancing societal trust. What is signalled (i.e. communicated) to the public is filtered by information transparency and disclosure guidelines, including privacy laws and the availability of evidence-based science. In the case of COVID-19, data related to infected patients are subject to these laws. PHAs strive to balance information transparency and the need for disclosure aligned to citizens-consumers right-to-know versus their need-to-know in what is often termed as “targeted transparency” on a specific issue. Furthermore, when PHAs signal health and safety guidelines to the public, these signals can be drowned out or distorted by signals from other sources, such as the media or PHAs in other countries. For instance, the widespread images of government leaders in some countries wearing medical masks are incongruent with many public health agencies’ guidelines that masks should only be worn if already ill. PHAs recommend “social distancing” and to avoid large or mass gatherings, yet these officials and experts are signalling in the media while sitting shoulder to shoulder. This is incongruent and a weak form of signalling.

When a crisis occurs, rational people behave irrationally

Governments have long signalled that citizen-consumers should have sufficient supplies of food, water and other vital goods, including first-aid kits and medicines in case of an emergency. However, when confronted with an actual emergency like COVID-19, where they have no personal control over the situation, rational citizen-consumers engage in irrational and unnecessary panic buying behaviours and hoarding. This behaviour creates supply chain imbalances by exceeding typical product demand forecasts. As a result, shelf stock replenishment and logistics supply capacity become constrained, leaving retailers with temporary stock-outs of food items like rice and pasta as well as utilitarian products such as toilet paper and cleaning materials. Importantly, hoarding large quantities of scarce goods deprives others of an adequate supply of necessities.

The dark side of humanity

In a crisis like COVID-19, the adverse effects of capitalism show as legitimate businesses may choose to engage in price-fixing, bid-rigging or price gouging, while some entrepreneurial citizens hoard and sell scarce goods online at massively inflated prices. Several governments, such as the U.K. and the U.S. and China, have issued strong signals by warning companies about anti-trust laws and cautioning against engaging in unethical behaviours.

Citizen-consumers hoarding may cause anti-social behaviours to erupt in public, as witnessed in some countries where police charged consumers after altercations over scarce utilitarian goods. Other antisocial and criminal behaviours included stealing scarce goods from other shoppers’ carts, shoplifting, office supply theft, theft of medical supplies from doctors’ clinics, and even armed robbery of 600 rolls of toilet paper in Hong Kong.

Note, even without an emergency like COVID-19, the impact of shoplifting, including organized crime retail theft, and other frauds in the U.S. supply chains, and at U.S. retailers was estimated at $46.8 billion in 2018. Much of these stolen goods may eventually be sold online to unsuspecting consumers or small businesses.

Empirical evidence on personal control deprivation

A recent study by Chen et al. (2017) provides insights into situations where citizen-consumers are deprived of personal control and may resort to panic buying and hoarding behaviours of utilitarian (i.e. food or cleaning materials associated with problem-solving) or hedonic goods (i.e. goods consumed for sensory pleasures like chocolate, or a new smartphone). As humans, we have an innate desire to control our environment and ensure favourable outcomes for our families. However, when potentially unfavourable situations arise like the COVID-19 crisis, they are profoundly felt by citizen-consumers as a loss of personal control. The situation worsens when authorities impose limits on our mobility and access to essential or non-essential services and resources. On top of this, we may have work constraints, leading to financial concerns and a fear that we can not feed, shelter and keep our families safe. Hence, one can easily see the link between our evolutionary response to act and problem-solve to assert control for ourselves and our families during a crisis. Thus, our impulse to buy and hoard utilitarian goods like food, toilet paper and cleaning supplies is associated with problem-solving, which compensates for our lack of personal control. The study noted that utilitarian products are perceived as less hedonistic and buying them is more easily justifiable (because they aid in crucial problem-solving). A further study by Kay et al. (2007), explains the lack of personal control fuels personal anxiety and discomfort levels.

“When personal control is threatened, people can preserve a sense of order by (a) perceiving patterns in noise or adhering to superstitions and conspiracies, (b) defending the legitimacy of the sociopolitical institutions that offer control, or (c) believing in an interventionist God.”

The following five points are recommendations for stakeholders to consider.

- We have excellent signalling by PHAs on “flattening the curve” for infection rates to ensure that our healthcare systems are not overwhelmed beyond their capacity. Businesses must also engage in signalling about supply-demand imbalances and assure citizen-consumers that an adequate supply of goods exists. Thus, flattening the demand curve is equally crucial as the spike in demand caused by panic buying exceeds retailers’ stock replenishment capacity. Importantly, governments and PHAs should not engage in signalling about food and utilitarian products as their signals on an area where they have no accountability or responsibility are considered weak.

- Signals can remind citizen-consumers that excess food can be donated to food banks. Charities and homeless shelters may have an urgent need for toilet rolls, sanitizers and disinfectants.

- Governments in all countries must protect their citizen-consumers from unethical business practices and send strong signals of market surveillance and enforcement action for anti-trust breaches. Their signalling should include a warning that the sale of counterfeit, unapproved and untested products will not be tolerated.

- Online platforms should monitor the sale of critical items such as toilet paper, cleaning materials, disinfectants and sanitizers to protect consumers from price-gouging. Sellers engaging in such practices should be delisted.

- All government agencies must ensure congruence in their signalling to citizen-consumers. More importantly, they must understand the noise and distortion that exists through mainstream and social media, which impacts the effectiveness of their signalling. They must be prepared to recalibrate their signals through citizen and business-sensing mechanisms.

About the Author:

John G. Keogh is a strategist, advisor and management science researcher with 30 years of executive leadership roles as director, VP and SVP in global supply chain management, information technology, technology consulting and supply chain standards. He is managing principal at Toronto-based, niche advisory and research firm Shantalla Inc. He holds a post-graduate diploma inmanagement, an MBA in management and a Master of Science in business and management research. He is a doctoral researcher focused on transparency and trust in food chains at Henley Business School, University of Reading using the lenses of agency theory, signalling theory and transactional cost theory.

Print this page