Alternatives to conventional meat, egg and dairy foods have been around for decades (margarine, for example) but developments in the past few years with plant-based meat and dairy products, in particular, have been keenly focused on enhancing the appeal of texture, taste and appearance. That no doubt has contributed to their recent popularity, and more importantly, to their future sustained success. Even Canada’s new food guide emphasizes plant-based nutrition, though more than likely Health Canada was thinking of veggies and grains in the more natural state as opposed to those which are more processed. Where’s the fun in that!

Although the sales of plant-based “meats” currently represent about two per cent of retail meat sales, the sector grew by nearly 37 per cent last year. This is a battle for market share and the threat thereof has put an already very protection-minded meat industry in high alert. This is particularly true in the U.S., where states have, or have proposed to, enact legislation requiring products marketed with meat terms to be labelled as imitations. In October, a federal bill was proposed in the United States House of Representatives to require imitation meat food products and beef to be labelled as imitations. If enacted, this would preempt state laws on the matter. It is also seen as a protective measure for the meat industry. An imitation food according to existing U.S. FDA legislation is a nutritionally inferior product. There are already rules in the U.S. for imitation food labelling.

In Canada, the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR) has specific nutritional and labelling requirements for foods that do not contain meat but have “the appearance of a meat product.” These rules date back to the 1970s and have not been amended since perhaps the late 1980s. If food is brown and in the shape of a patty or stuffed in a casing like a hot dog, it “has the appearance of a meat product.” This would trigger nutritional requirements related to protein, fat, vitamins and minerals. Such products are to be labelled as “simulated (naming the meat/poultry).” To make it even more clear, the labels of such products must include the statement “contains no meat/poultry” as the case may be.

In contrast, other than margarine which is subject to a standard of composition, there are no explicit federal rules concerning mandatory nutritional or labelling of alternative dairy products like milk and cheese. There are a few interim marketing authorizations (IMA), issued under the FDR, that provide for the optional addition of vitamins and minerals to vegetable-based or vegetable and to milk-based products, which resemble cheese, and the addition of vitamins and minerals to plant-based beverages like fortified soy beverages. The provision in the FDR for Health Canada to issue IMAs was repealed in 2012 and since then all IMAs have expired. Despite this, Health Canada has noted that they will respect the IMAs until they formalize changes to the FDR. That process is now long overdue and is compounded by the issuances of many temporary marketing authorizations under the FDR, like supplemented foods and energy beverages to mention a few, also waiting to see modernization. Formal changes are needed, as foods in Canada may not contain added vitamins, minerals or amino acids unless the FDR provides for this type of addition or unless some relief like and IMA or TMA is provided. That restricts the opportunity for alternative products to be formulated to be nutritionally equivalent to their counterparts.

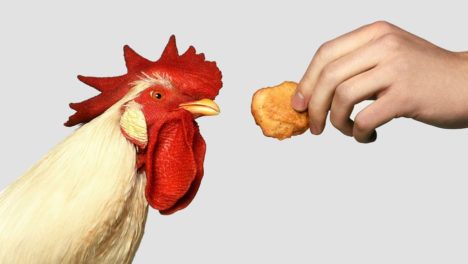

As 2020 approaches, the question of whether the simulated meat regulations are still relevant is being asked. As the current experience in the U.S. shows, consumers know vegetarian products do not contain meat. Calling it a “vegetarian burger” is a real giveaway. Plant-based manufacturers see terms like “simulated” or “imitation” as disparaging to their products. The meat and dairy industry sees these as needed to protect the identity of their products. For consumers, the question might be whether it’s still relevant to compare the nutritional equivalency of these plant-based foods?

The current regulations are an obstacle for the food industry to meet the demand of providing alternative plant-based foods. Why, in the case of simulated meat, are rules mandatory but not so for dairy food alternatives? A consistent approach would be a fresh start. The definition, “has the appearance of a meat product,” can be broadly interpreted, forcing foods to be captured as simulated meat just based on appearances. Perhaps it’s time to let the concept of “resembles” slip into history. Plant-based foods need to have room to establish their own identity, outside of being caught up in the “resembles” trap. That would be a step forward but doesn’t address the nutritional equivalency question. Foods that are represented as substitutes should be nutritionally equivalent, and regulations should make accommodations for this.

Nutritionally equivalent foods should not have to be labelled in an inferior way. The current IMA for fortified plant-based beverages requires such products to be identified with a common name such as “fortified soy beverage,” to distinguish it from the unenriched form. Those that are enriched that do meet protein requirements are required to be labelled as “not a source of protein.” Those that are enriched can be represented as an alternative to milk and those that are not, cannot. For foods that voluntarily use designated meat or dairy terms like cheese, then perhaps these should be labelled as substitutes if equivalent or imitation if not.

The plant-based beverage IMA is old, but it may still serve as a balanced model to build on in modernizing the rules on the imitation game.

Print this page