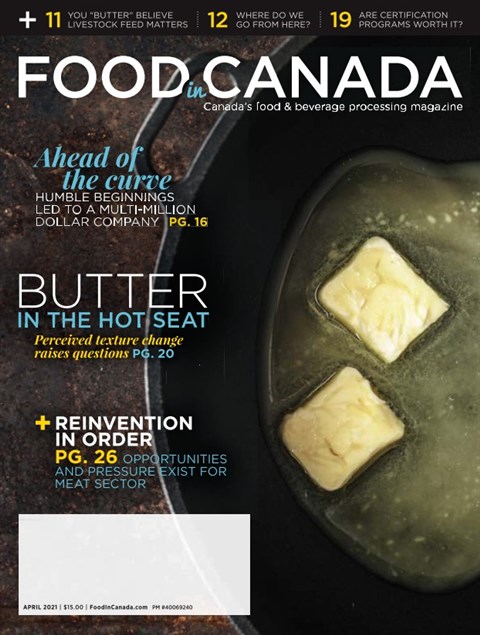

Butter in the hot seat – Cover story – April 2021

Food in Canada Staff

When demand surges for a Canadian food product, the Canadian food system responds swiftly, down to the farm level. For Canada’s dairy industry however, response to a rise in demand for butter starting in 2020 has had unintended consequences, but it has also resulted in valuable lessons for that sector, and for the entire food system in Canada and beyond.

As the pandemic progressed last year, massive numbers of people staying at home resulted in a large surge in demand for ingredients used in baking and cooking such as butter. To meet this demand, some Canadian dairy farmers may have started feeding imported palm oil ingredients, or more of them, to their cattle, because this feed ingredient causes production of milk with a higher fat content (milk fat is the main ingredient in butter). Demand appeared, demand was met, everyone wins, end of story.

However, by late 2020, discussions started popping up online about butter not softening like normal at room temperature. By February 2021, the story had exploded on Twitter and elsewhere. Serious questions were asked about health, our food system, food science and public trust. Media outlets in Canada and beyond ran many stories on the topic.

That same month, Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, perhaps Canada’s most well-known food industry analyst and senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University, wrote an article which was widely shared. In it, he states a belief that much of Canada’s butter has changed, and confirms that he’s done tests with colleagues at the University of Guelph which make him confident about that conclusion. And while he stresses that he’s never said this change was due to feeding palm oil to lactating cows, he challenges us to think it through. “It could also be due to genetics, other supplements, processing or other factors, but we have to ask, how was it possible for Canadian butter retail sales increased by 26 per cent in 2020 in Canada, according to NeilsenIQ, with only a small percentage of cows added to the national milking herd? That’s a very large amount, and it rules out things like genetics.”

In response to the situation, in February the Quebec dairy producers’ association has called for a stop in the use of palm oil. Agropur, a large Quebec dairy co-operative, did not respond to Food in Canada inquiries. Dairy Farmers of Canada (DFC) released a statement explaining that feeding palm oil “helps provide energy to cows and no undesirable effects have been identified arising from its use.” Shortly after, DFC recommended that producers stop feeding it to their cows, and that the ingredient would undergo a full scientific assessment. It established a working group in mid-March, including Dairy Processors Association of Canada (DPAC), academics and more.

While palm oil is a CFIA-approved feed ingredient for cows, Charlebois noted in his article that little research has been conducted on its effects on cow or human health. “What we do know is that palm oil may increase certain heart disease risk factors in some people,” he wrote, adding that “the effects of palm oil production on the environment, health and lives of indigenous people in different parts of the world are well documented and deeply concerning.”

Canada’s dairy industry, he wrote, is very image-conscious and “does not want this story to come out in the open, but now it has. Many dairy farmers want the use of palm oil to stop. Not only does it compromise the quality of dairy products many Canadians love, but it also breaches the moral contract between the dairy industry and Canadians.”

THE PUBLIC ARENA

There are several serious public trust issues here. Canadians have been surprised and upset that the apparent composition (and useability) of a very traditional product appears to have been modified without their knowledge — and with a substance that has some questionable health and sustainability aspects. Some feel their tax dollars are being unwittingly spent on subsidizing an industry that has been hiding practices with regard to butter, and may also have negatively affected their health.

Certainly, consumer interest in dietary fat has never been higher. In July 2020, results of a U.S. survey conducted by the International Food Information Council were released, showing that almost 40 per cent of respondents had a less favourable view of saturated fat than they did in 2010 (palm oil contains about 50 per cent saturated fat.) On a global scale, according to the newest annual “FATitudes” survey released in May 2020 from Cargill, about 70 per cent of consumers closely monitor the type and amount of fat and oil in their packaged food.

DFC working group spokesperson Adam Taylor points to many parts of a March 4 panel discussion (available on YouTube) involving four Canadian researchers on the fat fed to dairy cows. University of Guelph professor Alejandro Marangoni (also a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Food, Health and Aging) criticizes the sensationalism and lack of science in public discourse. At minute 35, he states that “people shouldn’t jump to conclusions and judge ethically something that is very complex. We eat palm oil morning, day and night, and we’re concerned about a few milligrams being fed to a cow. I think that we should be concerned about sustainability, but maybe we should eat less Twinkies,” a product known for containing unhealthy fats like palm oil.

It’s also safe to say that palm oil would not likely be identified by typical Canadians as a dairy cow feed ingredient, and some Canadian consumers have been surprised that this imported feed ingredient is available to farmers to increase milk fat content; they had perhaps perceived Canadian butter as made with all-Canadian feed ingredients, grown on Canadian farms.

The fact that the Canadian dairy industry has worked hard to present its products as Canadian “through and through,” says Charlebois, has resulted in it being “severely embarrassed” by this situation. “That’s their vision, but now consumers know that Canadian cows are consuming imported ingredients with health and environmental baggage,” he says. “The whole ‘blue cow’ logo and campaign seems like a farce. I’m troubled by this on many fronts. Dairy farmers seem to forget they exist in a highly-compensated and protected system. It’s really the first time they’ve had to face a transparency issue on this scale.”

PROCESSORS’ VIEW

DPAC believes it’s too early to tell if the pandemic has had an impact on butter consistency and saturated fat levels. “With respect to testing of finished products, including butter, dairy processors carry out their own internal testing on an on-going basis… That said, we are not aware of any data series related specifically to the fatty acid profile of dairy products that is collected on an ongoing basis by processors,” explains DPAC public affairs and operations co-ordinator Amélie Baillargeon.

With regard to whether any differences in butter processing would be needed if milk fat contains more saturated fat, she says “it is our understanding that certain processing techniques can be used to match the fat composition in raw milk in order to optimize butter consistency… what we have heard from our members is that there haven’t been changes to the way that butter is produced.”

Baillargeon also notes that while DPAC is aware of technology that’s used in places like New Zealand to detect palm fat or higher-than-normal saturated fat levels in milk that arrives at the plant, “for Canada, the first step is fully understanding the issue, the use and impact that palmitic acid supplements and/or other contributing factors have on butter consistency.” She adds that “dairy processors are watching this situation carefully. We have heard concerns from some consumers about the use of palmitic acid supplements in cow’s feed and we take their comments very seriously.”

MOVING ON?

John Jamieson, president & CEO of the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity, notes that “unfortunately, the myriad of opinions and speculation on the topic may be confusing to consumers as they try to sort out who is a trusted source of information to make the most informed decision when it comes to their butter.” He says the challenge of finding who is a trusted source of information “is really where the damage to public trust will be.”

He believes that “if the sector takes a candid approach and admits wrongdoing, most people will accept this. The sector then needs to follow with corrective actions. I do not think the public expects perfection, but I do think they expect progress, a commitment and actions that lead to continuous improvement. I also believe that the food industry is only as good as its weakest link.” He believes also that this particular breach of trust “is being repaired correctly with the response from the dairy sector to complete a thorough examination on the product.”

Charlebois has a different view. “Buttergate is not a controversy but rather a symptom of a systemic transparency problem, and I’m not sure the industry is going to learn from this,” he says. “I submitted a report to them March 14 with all the science we have. We want to help this industry, not harm it. I think the dairy industry will recover from this, but given how Canadians have reacted to this situation, I think it should not bother to study palmitic ingredients but simply stop feeding them to dairy cows, and move on.”

— BY TREENA HEIN —

Print this page