What’s really behind higher milk prices

By Dr. Sylvain Charlebois

Processing Dairy Canadian Dairy Commission Dr. Sylvain Charlebois Editor pick

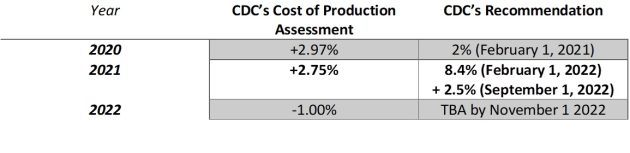

Every year, the Canadian Dairy Commission (CDC), a branch of the Federal government, hires external consultants to assess the cost of producing milk on the farm. The CDC has never released any data about costing and has recommended farm milk price increases most years, eventually impacting retail prices and Canadian families. Since February, on average, dairy product prices have gone up by anywhere from 10 to 15 per cent. However, some CDC data was recently leaked, which gives us a better picture of how the cost of milk production is determined. The CDC has announced not one but two hikes this year: the first was a record-breaking 8.4 per cent in February, and the second, 2.5 per cent, will come into effect September 1. Based on the CDC’s leaked data, it appears that these increases are simply unfounded.

The CDC will normally base its recommendations on an annual survey conducted by hired consultants. They survey over 200 dairy farms all over the country to measure the cost of producing milk. Recently, the results from the 2021 survey were presented in a confidential meeting. The standardized cost of production went from $85.42 per hectolitre to $84.57 per hectolitre, a one per cent drop. Notwithstanding this year’s record increase announced in October 2021, the CDC increased milk prices by two per cent in 2020. All that was going on while the cost to produce a hectolitre was either slightly increasing or dropping in Canada.

According to the report, some costs did go up, like feed at $0.76 per hectolitre, and fuel at $0.28 per hectolitre. But other costs per unit went down, outweighing items that cost more. For example, standardized fixed-rate labour and labour in general dropped -$0.91 per hectolitre, and standardized capital costs dropped -$0.54 per hectolitre. The CDC’s pricing formula includes all aspects of dairy farming, from infrastructure to veterinary medicine, promotion, everything, with the exception of subsidies given to dairy farmers for hypothetical losses incurred from trade deals. The margin of error for this year’s survey was 2.06 per cent, lower than in 2020 (2.35 per cent).

That said, early results of the 2022 survey suggest that costs are going up, but that should impact prices in 2023, not this year. Most disappointing is the fact that the Canadian Dairy Commission, the government, likely succumbed to pressures coming from the dairy industry by increasing farmgate prices without any sound empirical data to justify increases. It’s all anecdotal. This points to how the CDC’s governance has become a reputational liability for the dairy industry and for Canadian consumers.

The idea that dairy production per unit can be less costly may sound counter intuitive. After all, inflation is affecting all aspects of our lives. Farmers, industry experts, and even the Canadian public bought in to the argument that everything is more expensive, even for dairy farmers. The reality though, is that many dairy farms are now operating with hardly any human beings around. Technology is taking care of the most intensive aspects of dairy farming. Dairy genetics have also come a long way. Some U.S. estimates suggest that the dairy industry is producing 60 per cent more milk with 30 per cent fewer cows compared to 50 years ago. According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canada was home to 977,000 dairy cows in 2021 while producing 95 million hectolitres of milk. In 1990, Canada had almost 1.4 million dairy cows and produced 73 million hectolitres of milk. That’s 43 per cent fewer cows, with an 31 per cent increase in production. That will bring costs down.

Last year’s “Buttergate” episode, when Canadians learned that dairy farmers were using imported palm oil derivatives from Indonesia or Malaysia to produce more butterfat, adheres to the same modus operandi. It not only made butter harder but using palmite is another method to decrease costs while generating more revenue. The practice was banned for a while, but dairy farmers are back at it again. The Dairy Farmers of Canada are only discouraging – not banning – the practice, as dairy farming is self-regulated with little governmental oversight on quality assurance.

Dairy farming is simply getting more efficient, generally, although two versions of farming are colliding in Canada’s dairy industry. On the one hand, many dairy farmers are investing in technology, making farms more efficient, bringing down the cost per unit produced. Most of these farms are west of Toronto, right through to British Columbia.

The farms east of Toronto will offer a very different scenario. These farms are much less efficient, smaller on average, and are just looking for “fair pricing” supported by the CDC’s focus on increasing prices, no matter what. Over the years, that “fair pricing” mentality has pushed farmgate milk prices higher. Most of these farms are in Eastern Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic. Quebec has half of all dairy farms in Canada. It’s no coincidence that most of the loudest voices defending supply management and our quota system come from that part of the country. As a result, milk prices in Canada are about 30 per cent higher that the world average.

This points to how the CDC is morally and ethically compromised. It needs to distance itself from the dairy sector immediately. More transparency and honesty and better communications would also improve the crown corporation’s public image. Most federal crown corporations have always been forthcoming with data to allow the Canadian public to understand and appreciate their work, but not the CDC.

To be clear here though, dairy farmers are victims as much as the Canadian public. Dairy farmers themselves, politicians, even the Minister of Agriculture Marie-Claude Bibeau have always been hypnotized by the CDC’s gibberish and numbers, and don’t fully understand the system, relying on Dairy Farmers of Canada’s loud and influential voice. It’s disappointing that we needed a leaked document to realize that recommendations given by the CDC are based on weak evidence and hearsay.

For years, many speculated that the CDC was misleading the public. Now we know that the Canadian dairy industry’s “smoking gun” was indeed real.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is professor and senior director, Agri-food Analytics Lab, Dalhousie University.

Print this page