‘Aspiring’ change

By Treena Hein

Food Trends Aspire Editor pick insect protein Ontario pet foodA young company in Ontario is on the cusp of changing the pet food landscape with insect protein

The house cricket thrives in low light and has an attractive nutritional profile. Photos courtesy Aspire

The house cricket thrives in low light and has an attractive nutritional profile. Photos courtesy Aspire Canadians may not typically associate crickets with pet food, but once they think about how insects are a natural food source for cats and dogs and understand their many health and sustainability benefits, the association swiftly becomes favourable. That’s what companies like Aspire are betting on, anyway. Of course, Aspire’s plans are backed up by years of intensive research into the nutritional value of crickets for pets (and humans), quality assurance and much more.

Companies like Aspire have found that products with insects are attractive to consumers—especially Millennials, for themselves and their ‘furkids’—because they’re very sustainable. A recent report from Future Market Insights predicts the growing demand for sustainable and organic pet food will propel global sales of insect-based pet food to USD17.29 billion by 2030.

The sustainability of insect farming is many-faceted. Insects convert feed into growth at a rate that’s light years ahead of even the best performers of all other livestock types (fish and chickens). Further, in the production of insects like black soldier flies (BSF), food waste is already being used as feed source. BC-based Enterra is currently building a new plant near Calgary, Alta., where it will use food waste to grow BSF to further meet market demand in the pet food, poultry feed and wild bird feed sectors here and in Europe. With some insects such as crickets, the waste (known as frass) makes outstanding fertilizer, providing a sort of circularity to insect farming, as well as adding another revenue stream for companies like Aspire.

It’s no wonder then that the use of crickets and other insects in pet food and in human food products is growing in Canada and beyond. As many of us already know, in some regions of the planet, insects have always been a staple in human diet.

Aspire’s London, Ont., plant is the world’s largest, fully automated cricket production and processing facility.

Company beginnings

All this was realized by a group of young and ambitious McGill University MBA students who founded Aspire in 2013: Mohammed Ashour (now Aspire CEO), Shobhita Soor, Gabriel Mott, Jesse Pearlstein, and Zev Thompson. Their quest to produce a high-quality protein with low environmental footprint would win them the Hult Prize that year.

Between then and now, however—Aspire is now headquartered where its new plant is located in London, Ont. —the firm has travelled the world.

In 2014, Aspire started a palm weevil larva pilot facility in Ghana with KNUST University, the first-of-its-kind in Africa (and now a spin-off called Legendary Foods Africa, where Soor is CEO). That same year, Aspire began conducting R&D in Mexico while launching a pilot cricket production facility in Austin, Texas. By 2017, Aspire had built a second pilot plant in Austin, which is also an R&D facility.

“There’s a strong open-mindedness with regards to food products in that city and it was—and still is—a very good business environment ‘match’ for us,” explains Ashour. “There, over five years, we did an enormous amount of R&D, refining systems and trialling technologies to achieve the right environmental conditions for the high quality and high yields we wanted, while remaining cost effective.”

At the same time, Aspire leaders were talking with pet food firms, and as early as 2017 they already had orders for volumes that would justify building a large plant.

“An investor encouraged us to look at southwestern Ontario,” says Ashour. “There were a growing number of funding opportunities from the federal government, which are an important consideration for any company, new or old. We visited several cities and London came out ahead. It offered us proximity to customers and feedstock suppliers and was also very attractive in terms of talent recruitment, company growth and local government support.”

Farming crickets

At the end of March 2022, the cutting-edge 150,000 sf plant was finished, with construction supported by $10 million from Sustainable Development Technologies Canada. Aspire also received $16.8 million from the feds (the NGEN Supercluster) to work with partners on automation of cricket processing. As the plant moves to full capacity by the end of 2022, it will produce 20,000 metric tonnes of product a year in whole crickets for the pet food market and frass. (Whole crickets provide pet food makers with maximum flexibility in their production processes.)

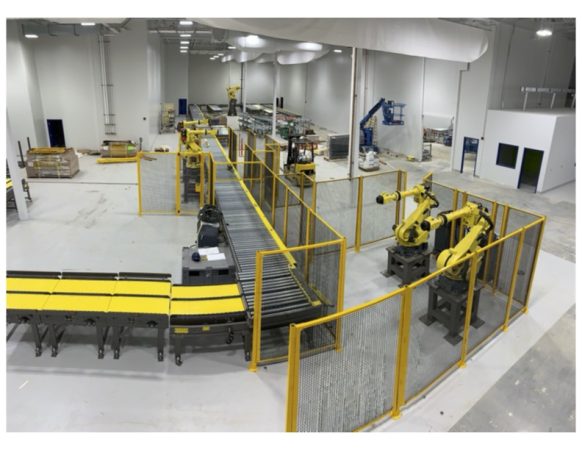

The London plant will be the world’s largest, fully automated cricket production and processing facility, leveraging all kinds of Industry 4.0 technologies such as robotics and artificial intelligence.

As Anne Waddell (Aspire’s director of government affairs) explains, the creation of the plant is backed by Aspire’s own R&D investments of over $20 million. “No company in the world has assembled a body of research on crickets that comes close,” she says. “We have 176 independent inventions and have acquired 11 patents.”

Aspire uses cutting-edge technology to harvest crickets that can be used in pet foods.

Products

The first target market for Aspire’s London-grown crickets is premium pet food, with protein that’s competitively priced compared to other complete proteins, and pound for pound, less fat and calories.

“While animal-based proteins are highly nutritious, ‘pet parents’ are increasingly concerned about sustainability and animal welfare,” explains Dr. Jenn MacLean, Aspire’s vice-president for research and innovation. “Plant-based proteins are sustainable and ethical but raise concerns about adequate nutrition for carnivorous pets.”

Eventually, Aspire will also target the human food market. “Crickets are not a novel food in North America,” Waddell explains. “The edible insect protein market is now growing at a rapid pace. Aspire cricket protein powder, made in Austin, goes into snacks and other products made by Hoppy Planet Foods and other companies.”

Strong interest in Aspire’s high-protein cricket powder has grown, says Ashour, because it’s odourless and tasteless. But he explains, “food-makers have been waiting for large volumes. I believe that within 10 years in Canada, we’ll see enormous production growth in this industry, with maturation on the regulatory side and entire research departments being created focused on food and feed uses for crickets and other insects. We’re planning several large plants in the next decade, in North America, the Middle East/North Africa region and Asia, and we’re only one company.”

Although much insect research has already been done by Aspire and others, there is much more to be discovered. “We’ve learned a lot,” says Ashour, “but there’s so much more to research in terms of the dietary needs of insects, their nutritional content, feed trials in dogs and cats to measure health benefits, the list goes on. The story of crickets so far has been one of high levels of protein and Vitamin B12, but preliminary research suggests there are digestive and immune benefits with consuming crickets as well. There are exciting times ahead and right now we are helping to establish the first ‘Canada Research Chair’ in insects for food and feed at Laval University, and a research program at Western University.”

Setting aside food and feed for a moment, Ashour notes other important possibilities of insect farming. “This is very exciting for me personally, to plan for the use of our insect production system to someday manufacture other valuable raw materials at scale,” he says. “There are 3 million insect species. We can’t begin to measure the potential for producing raw materials for pharmaceuticals, textiles, cosmetics products, surgical materials, inks and dyes, the sky is the limit. But it all requires a successful model for large-scale production, which we have already successfully created.”

This article was originally published in the June/July 2022 issue of Food in Canada.

Print this page